Six miles south of New Iberia, Louisiana sits Avery Island, best known as the home of Tabasco Pepper Sauce. Like the pepper in the famous sauce's name, the designation "island" is something of a misnomer. Surrounded by bayous, salt marshes, and swamps, Avery Island is actually 2,200 acres of lush semi-tropical marshland set atop an eight-mile-deep natural salt dome. It was here that, in 1868, Edward McIlhenny, a former New Orleans banker left destitute by the Civil War, began manufacturing Tabasco, making it one of the oldest sauce brands in the country. Initially sold locally in cologne bottles, Tabasco has since grown to become a global commodity, currently available in 192 countries and so ubiquitous that, for many people, the brand's name is synonymous with hot sauce itself.

I first became aware of Avery Island while doing research for a novel. Set in 1914, the story centers around the experiences of a man who invents a meat sauce which, like Tabasco, becomes an extremely popular national brand. One of the things I wanted to explore when I wrote the book was how the increased circulation and distribution of commodities in the early 20th century impacted ideas about identity, community and local culture. Tabasco—which is often associated with Louisiana identity and which was emerging as a global brand during the same period in which my novel is set—became a focal point of a more specific inquiry into the intersecting symbolism of food as both a commodity and source of sustenance.

Gulf Coast

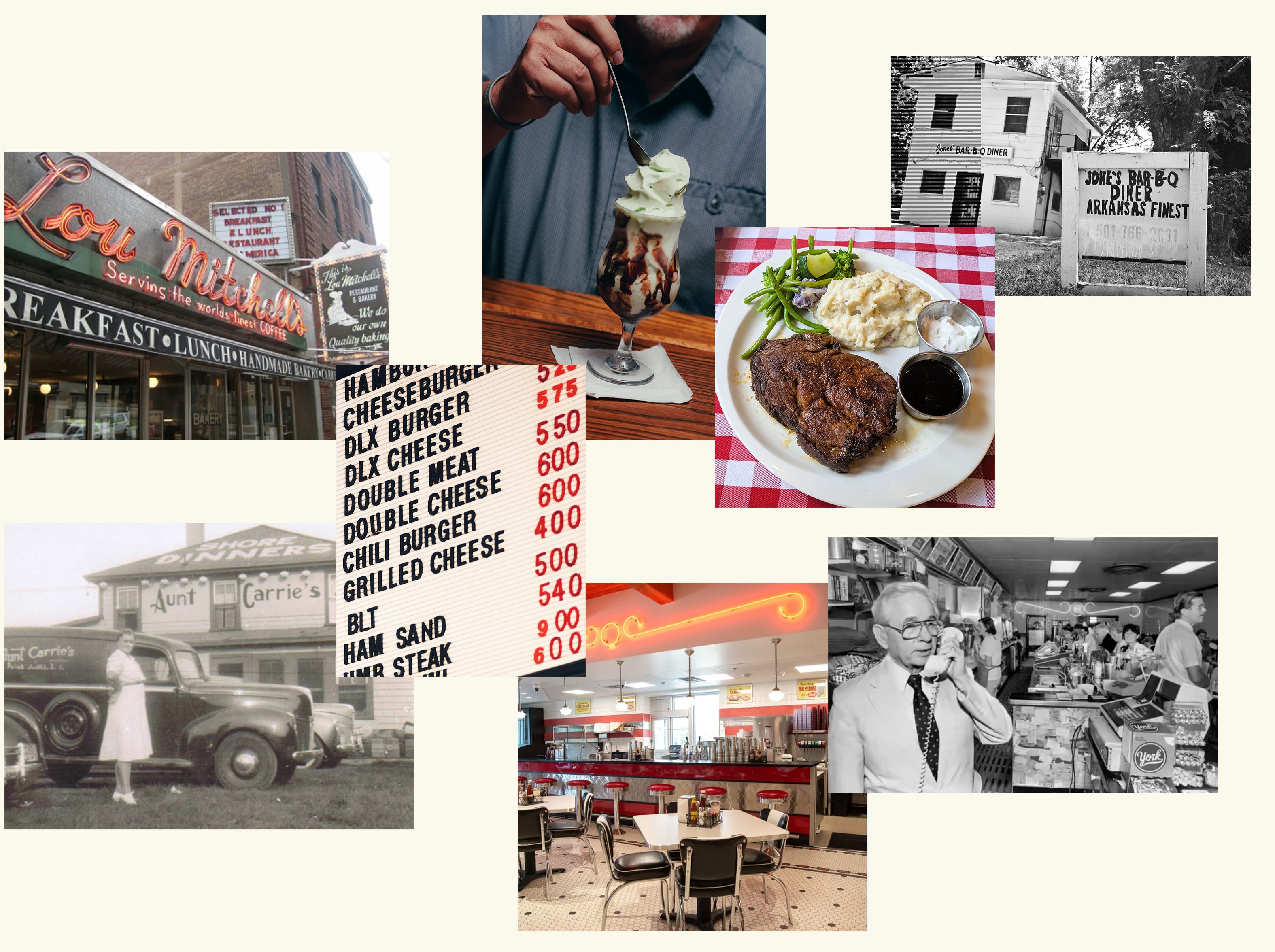

Field Guide

Want more secret intel from our Gulf Coast field guide? Dive deeper into a world of seafood shacks, dive bars, writers, cigar makers, secret beaches and salty small towns.

Incredibly, the Tabasco company is still family-owned and continues to operate out of Avery Island. And so a visit offered the opportunity to witness firsthand how the sauce is made. The on-site museum documents the story of how McIlhenny, after years of experimentation, determined that aging his sauce greatly improved its specific taste. His method of production involved grinding the chilis into a mash, mixing it with the island's natural rock salt and aging it in jars for thirty days. Vinegar was then added, and the sauce was pickled for another month.

A tour of the factory demonstrated how this original process continues to inform production today. The period of fermentation has been extended from its initial two months to an average of three years and, in order to keep up with demand, the chilis are now farmed in various locations in Latin America. But all of the seeds still originate from Avery Island, and once the chilis are cultivated overseas they are sent back to be mixed with salt (mined from underneath the dome) and aged in large oak barrels. The company has been able to continue to operate out of its original location all while manufacturing up to 750,000 of sauce bottles per day.

The McIlhenny family's influence resonates on the island, as does a legacy of preservation. Just across the road from the Tabasco facility is Jungle Gardens, a 170-acre botanical garden and wildlife sanctuary that stretches along the Petit Anse Bayou and was established by Ned McIlhenny, son of the McIlhenny Company's founder. Within Jungle Gardens is Bird City, one of the oldest bird sanctuaries in the United States, often credited with having saved the snowy white egret from extinction in the 1920s, when the population was threatened due to the overuse of their feathers in the making of ladies' hats. Today thousands of egrets can be seen on the island as well as numerous other species of animals including white tailed deer, otters, muskrats, alligators and Louisiana black bear.

All of this emphasis on preservation seemed fitting of a place literally made of salt. It occurred to me that the only two other ingredients of Tabasco—chili and vinegar—are, of course, preservatives themselves. In a slight deviation from the focus of my novel, I began to consider how the cultural histories of all of these ingredients, and in particular chilis, told a much broader story, through the central role they have long played in mediated the circulation of food products themselves.

Capsaicin, the unique chemical substance that makes chilis "hot," is, like salt and vinegar, a powerful antimicrobial. Chili sauce not only makes food taste better, it also helps keep good food from going bad—a fact that has contributed greatly to hot sauce's appeal, in various incarnations, throughout the world.

All of these incarnations are traceable back to the Americas. One of the world's earliest cultivated crops, the chili is indigenous to the Americas and, like the tomato, potato and corn, made its way into the cuisines of Europe, Asia and Africa through various trade routes at the service of slavery, colonialism and global commerce. Given the chili's current associations with a wide variety of cuisines, the specificity of its origins in Mesoamerica is frequently obscured by its identification as a pepper—a misnomer attributed to a confused Columbus who associated it with peppercorn because of its comparable "spicy taste".

Long before Columbus' arrival, native Mesoamericans recognized the chili's usefulness as medicine. Its association with U.S. southern and African American cuisine is in part an expression of cultural affinity, as prior to its introduction in Africa by the Portuguese, the people of West and Central Africa used strong spices not only to flavor foods but as a way to treat various ailments. This affinity for the spicy was in part transferred to the chili during the slave trade, when some slave owners actively encouraged the consumption of chilis, based on their own beliefs that it kept slaves healthy.

In Louisiana, its broader consumption in the mid-19th century is often associated with the advocacy of a man named Maunsel White, a sugar planter who firmly believed that chilis had kept his slaves from getting sick during a cholera outbreak. White created several sauces made from different chilis, including the distinctive tabasco variety he introduced some twenty years before McIlhenny began bottling his. White sold his sauces to oyster bars while actively promoting their consumption among the white slaveholding aristocracy, often distributing bottles of it as gifts to his friends who included Andrew Jackson.

By the mid 19th century, homemade pepper sauces were popular throughout Louisiana, crafted from recipes that utilized a wide variety of supplemental ingredients and modes of preparation. Most of these recipes featured the more commonly accessible Cayenne chili, however, and so McIlhenny's product, heralding the use of the distinctive tabasco, was initially a way to distinguish itself in an already crowded field.

Thus, the product most associated with regional identity was originally an eccentric variant. It now stands as one of the most iconic emblems of Louisiana culture despite being named for a region of Mexico that Edward McIlhenny never even visited. According to legend, McIlhenny received the original, unidentified seeds as a gift from a confederate soldier who had recently visited Mexico; he planted them on Avery Island, at the time a sugar plantation owned by his wife's family. He then forgot about them until he returned following the Civil War and found the chilis, the basis of the family fortune, growing wild.

The specifics of this story are, like many official narratives of history, disputed. It gives no account of White's previous experiments with tabasco or of the contributions of both Indigenous people and African Americans to both knowledge of and efforts to cultivate the chili more broadly. And yet it is a fascinating story, because of the ways it both stubbornly deflects and embodies its own contradictions about identity, culture, and the unextractable intersection between the global and the local. Which in turn makes Tabasco—as a highly refined preservative, source of sustenance and carefully curated brand—a fitting emblem for Louisiana itself.

About the author

Ladee Hubbard is the author of The Talented Ribkins, which received the 2018 Ernest J. Gaines Award for Literary Excellence, and The Rib King. Born in Massachusetts and raised in the U.S. Virgin Islands and Florida, She currently lives in New Orleans with her husband and three children.

Ladee Hubbard is the author of The Talented Ribkins, which received the 2018 Ernest J. Gaines Award for Literary Excellence, and The Rib King. Born in Massachusetts and raised in the U.S. Virgin Islands and Florida, She currently lives in New Orleans with her husband and three children.