The Lost Black History of the American West

HOW A SELF-TAUGHT WRITER BROUGHT CALIFORNIA’S BLACK PIONEERS BACK INTO THE GOLDEN STATE’S TALE.

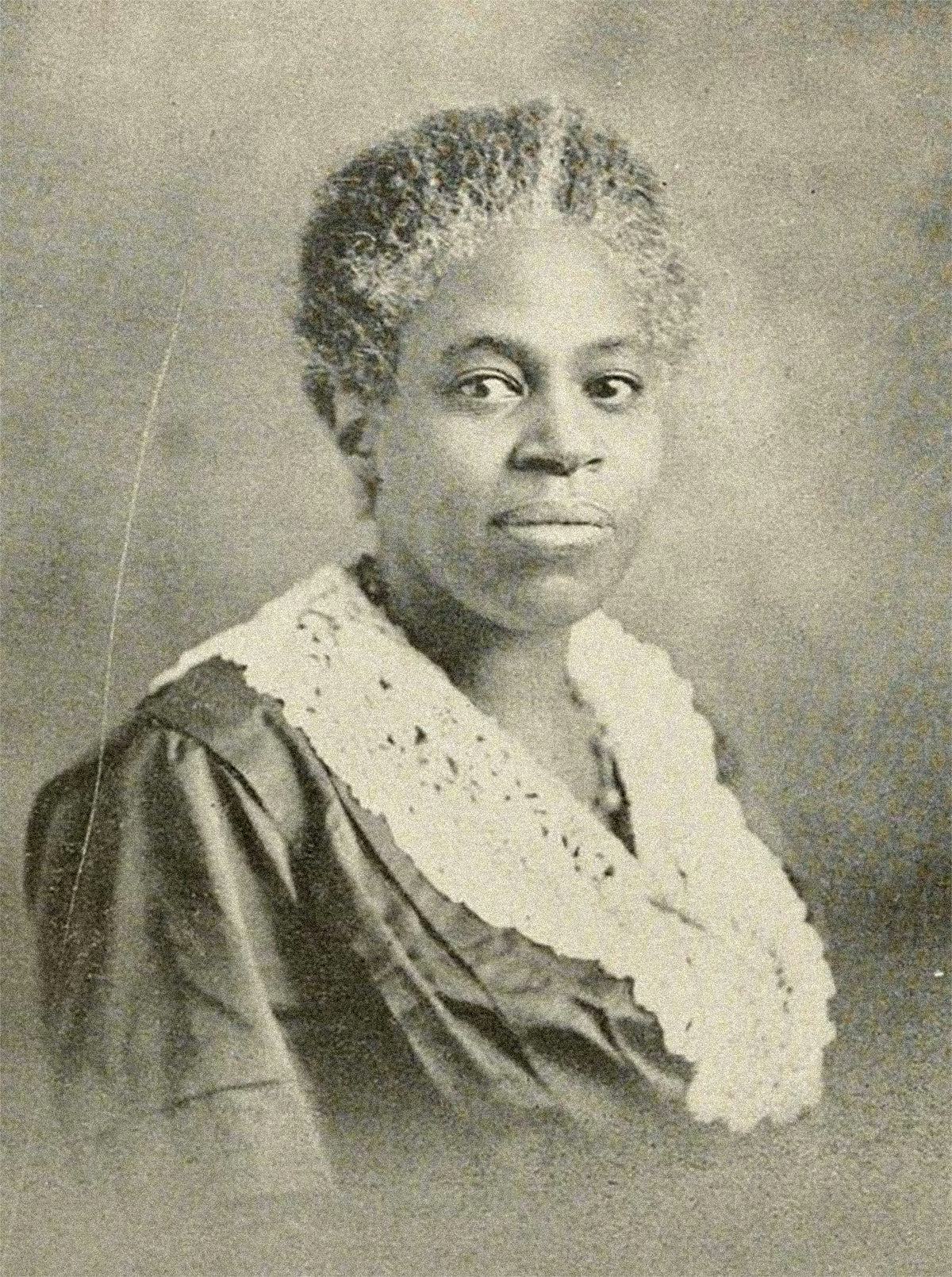

Delilah L. Beasley, Negro Trailblazers of California (1919) | Library of Congress

I grew up in the mountains of San Gabriel Valley, in the suburbs of West Covina. Like a lot of children in the ’70s and ’80s, television was my babysitter. I watched mostly reruns: Gunsmoke, The Rifleman, Bonanza, The Big Valley, Maverick, The Lone Ranger, The Wild Wild West and, most of all, Little House on the Prairie. I would sit inches away from the screen, enchanted, wanting to be in the frontier worlds I saw. I longed to climb through the set and ride a horse or pump water from a well, pull a gun from my holster and fire. But I was always flummoxed by an incongruity. To watch those shows was inevitably to equate pioneers and cowboys with whiteness.

I placed myself in these vast stretches of land, in the occasional saloon, striking gold as I mined in my calico dress. But in my young mind, I made an exception to the facts in order to accommodate my fantasy. It was like imagining my human self on the moon, except I was the Martian. I learned from these shows that Black cowboys didn’t exist and neither did Black pioneers, not really. When a Black person did make an appearance, it struck me as intrusive, like when a little Black boy was found hiding in Laura Ingalls Wilder’s barn. Laura couldn’t believe her eyes, and neither could I. My 12-year-old self found it lacking in verisimilitude.

But of course TV is simply a re-inscription of what white America would have us believe–that the West was won absent any Blackness. In fact, African Americans are inextricable from that chapter of history, and from California’s origins in particular. They participated in expeditions that would lead to the state’s discovery, before it had a name. William Alexander Leidesdorff, a biracial businessman, helped found the city that became San Francisco. Enslaved miners brought to California circa 1849–though slavery was illegal–worked and generated the wealth that allowed California to become a viable state. And there were the Black men who rode in the Pony Express, closing the gap between the East and West.

Though I would glean none of this from Bonanza or Little House on the Prairie, it turns out someone had worked tirelessly to bring such contributions to light. Delilah L. Beasley, an autodidactic historian, lifelong newspaper woman and activist, published The Negro Trail Blazers of California in 1919. Hers was a mission no one else had undertaken: documenting California’s early Black pioneers and writing a comprehensive history of Black people in the state of California. As groundbreaking as her work was, it was wholly ignored by popular culture. A native Californian myself, I’d never heard of her until relatively recently. I spent a year researching Beasley and came to see that she, like her subjects, was a forgotten pioneer.

Born in 1867 in Ohio, she lost her parents in quick succession as a teenager. She fell in love with California on an early trip here and became part of the African American migration west. She built a jumbled existence here, working variously as a maid, masseuse, manicurist and nurse, even while writing for newspapers. At one point, researching in UC Berkeley’s archives for her book, she worked as a cook in the university’s archives, “browning the fried potatoes and practicing scalp massage among the students.”

Relying largely on the kindness of friends and benefactors, Beasley traveled all over California, interviewing Black pioneers and historians. Her queries were often met with disinterest by white interviewees and historians charged with documenting the annals of California. Of course this only reinforced her mission: combating the willful erasure of African Americans’ contributions to the West. The pages of The Negro Trail Blazers dare readers to refute the facts: Say there were no Negro pioneers here, no Black artists and visionaries, no explorers–my life’s work will prove you wrong. Beasley didn’t write like a historian–she wrote like a woman who understood how uninterested white Americans were in African American history. No detail was too small or tangential. She lists trailblazers, name after name, accomplishment after accolade, dating back to one of the expeditions that eventually led to the discovery of California, in 1535. (Apparently, such facts were still contested, so Beasley found someone to translate Spanish documents. “[In] a desire to remove any possible doubt as to the Negro Priest being with Coronado’s expedition of exploration in an effort to discover California,” she writes, “the writer has been fortunate in having a friend, Miss Buth Masengale, voluntarily to offer to translate some Spanish documents … It seems passing strange that after hundreds of years, a colored girl and a native daughter of California should be the one to translate this document …”).

Beasley includes interviews with people who made epic journeys across the plains, narrowly avoiding massacres by indigenous populations in some cases. She writes of California’s first Black miner, Waller Jackson, and another, Elige Booth, who described the poor treatment of Black miners, adding that “a man was a man, even if he was a colored miner.” We learn of Annie Peters, who came to California in 1851 and was the oldest living pioneer of color in 1918. Beasley describes the struggles of Negro pioneers, who sought freedom from racial persecution in the West, often finding it elusive.

Beasley worked through near-death illness and poverty. In a letter to W.E.B. DuBois, she complained that she was tired of her shabby wool coat, whose worn lining she’d restitched many times. She used it as a blanket when she traveled California by train, unable to afford a sleeper car–or a new coat. She literally gave her flesh and blood to the project, suffering a toe amputation after an accident during her travels.

For all that, the book did not sell as she had hoped. Her ambition was to have a copy of The Negro Trail Blazers of California in every library in California. Instead, bad reviews and lack of interest pushed the volume into obscurity. Except for the academics and scholars who later excavated her life, Beasley suffered the same fate. She died a mostly unknown figure, at the Fairmont Hospital in San Leandro, California, on August 18, 1934. Her tombstone is carved, in somber Black marble, with the wrong date of her birth.

Anyone curious to know about California’s invisible history can finally find her book, and sift through the names and dates and seemingly incongruous facts for a fuller picture of the West–and of how California came to be. These souls will come to you like apparitions, tapping your shoulder to insist on a place in your memory. One can only imagine what those narratives meant to Beasley, who created a book with such urgent and crowded detail that one reviewer called it a “hodge podge.” But she felt she was writing for everyday people, and that she owed it to future generations of African Americans to tell of their struggles. She regarded this not as a burden but a gift, one she was thankful to give. The Negro Trail Blazers of California opens with a simple inscription: “Ever grateful. Delilah L. Beasley.”

But I am grateful to her, now that I’ve researched her life as a pioneer in her own right and read about the countless Black pioneers who are essential to California’s origin story. Why, only in 2019, did I discover her and her stories? While I was staring at my television decades into the future that Beasley imagined–in the very state she wrote about, dismissing the few Black pioneers I saw, unable to see myself in these stories–her book was sitting in a library somewhere, obscured, trying to tell me that African Americans were at the center of the story, not the margins.

Beasley and I are 100 years apart; she was born in 1867, and I in 1967. I’m a writer from California. I understand her urgency. There are so many stories about African Americans I don’t see in the literature, and in California literature particularly. I often wonder: How will people in the future know who Black people were and are, in this place where I was born, this place I claim as mine, that I love as much as Beasley did, if the stories don’t tell them?

This is one.

This essay originally appeared in Wildsam California, a road trip guide to the Golden State, first published in 2020, and updated in 2022.

Dana Johnson is the author of the short story collection In the Not Quite Dark. She is also the author of Break Any Woman Down, winner of the Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction, and the novel Elsewhere, California. Born and raised in and around Los Angeles, she is a professor of English at the University of Southern California.

Dana Johnson is the author of the short story collection In the Not Quite Dark. She is also the author of Break Any Woman Down, winner of the Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction, and the novel Elsewhere, California. Born and raised in and around Los Angeles, she is a professor of English at the University of Southern California.