The Groove

One Texas troubadour spanned the spectrum of Lone Star music, from garage rock to country gigs. His name was Doug Sahm.

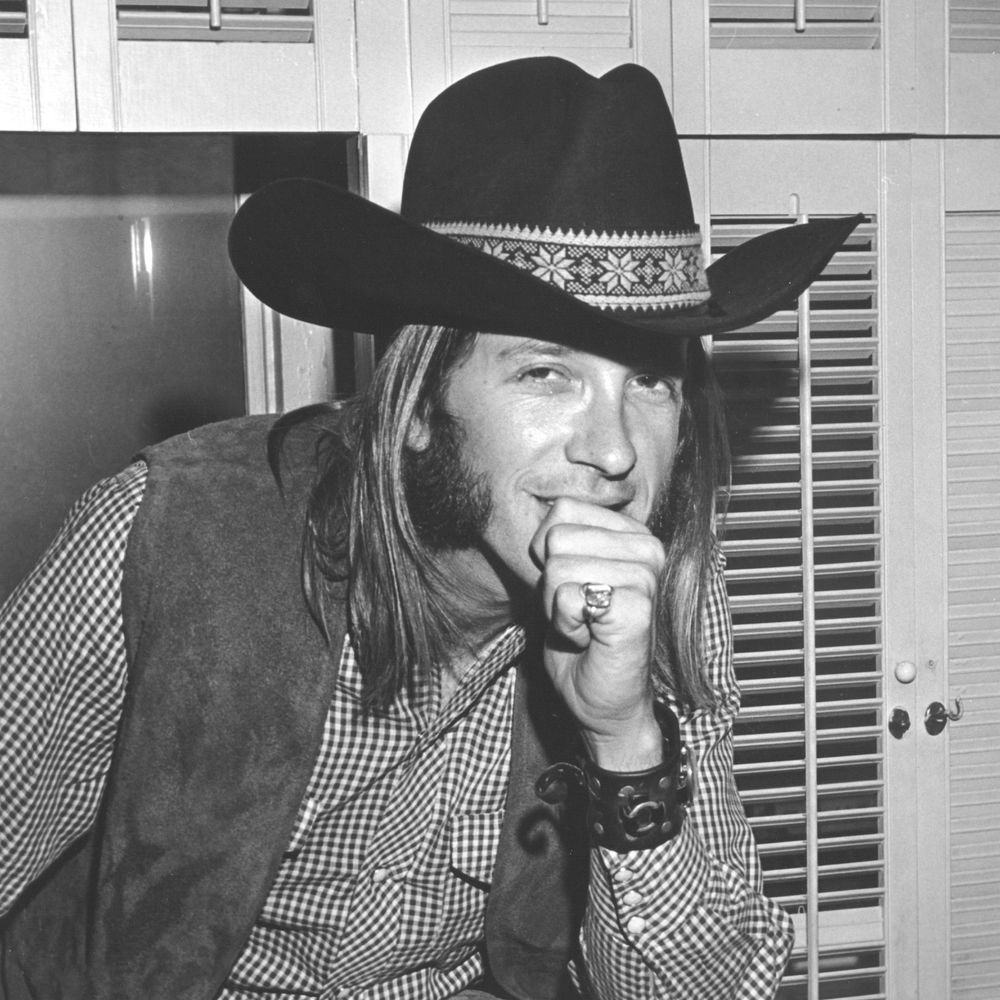

Doug Sahm in 1973 | Atlantic Records

THE MOON HUNG FULL, bright and high over the Chihuahuan Desert floor like a bare light bulb illuminating a small-town sheriff’s drunk tank, an observation I would have been smart to consider at the time. I was one of three dudes in a beat up old Land Cruiser, barreling up a West Texas byway at 3:00 A.M. after a long day spent satisfying Texan rites of passage. We’d fed beer to the goat mayor of Lajitas, Clay Henry; paid fifty cents for a canoe ride twenty feet across the Rio Grande to eat dirty tacos in Old Mexico; and traded tequila shots with people who live in abandoned mine shafts at both bars in Terlingua. Now we were headed back to a trailer park ten miles away in Study Butte, where our girlfriends had wisely gone to bed hours ago.

The moonlight was sufficient to cast grey shadows off the scattered ocotillo and salt cedar scrub, though probably not bright enough to be driving without headlights. Still, that’s how we were doing it, with no regard for the law or cows crossing the road. Our fates had been placed in the hands of the great Doug Sahm, patron saint of far out trips. If we’d found a tiny alabaster statuette in his likeness—black cowboy hat, long hair, flowing scarf and a duster—we’d have mounted it on the dashboard. But we didn’t need that either. We had his CD in the stereo.

The song was a timeless slice of Tex-Mex pop called “Mendocino.” It opened with an acoustic guitar strummed in a polka rhythm that seemed to have followed us up from the border. Doug spoke over the intro in a husky drawl. “The Sir Douglas Quintet is back and we’d like to thank all our beautiful friends all over the country for all the beautiful vibrations. We love you.” Then Doug started to sing in a soul-shouter’s rasp as his lifelong sideman, Augie Meyers, kicked off a bumping organ riff that was sweet as Big Red.

Teeny Bopper, my teenage lover

I caught your waves last night

It sent my mind to wonderin'.

You're such a groove

Please don't move

Please stay in my love house by the river.

The moment was perfect, the kind that gives you faith that, sometimes, the world really will just get out of your way. When the song ended, we hit it again, and this time it played out with us parked in front of the trailers. A light came on in a bedroom. Clearly, one of us was headed for hot water. We looked at each other, cracked open another brew, and hit Doug again.

DOUG SAHM MOVED to Austin sometime in or around late 1971 for the stated reason that he was looking for a new groove. In Doug terms, that made perfect sense. All he was ever looking for was one of two things, a hit song or a new groove. The search for the former proved fruitful enough, taking him to the top of the charts and the Grammy winner’s podium. But the quest for the latter was more subtle, more challenging. “There’s always something trying to disrupt the groove,” he used to say in his hopped-up hippie speak. “But the groove’s at the center, man. It’s the sun. Everything revolves around the groove.”

A white-boy son of San Antonio’s Eastside neighborhood, he’d picked up the musical styles bouncing around S.A. in the forties—conjunto, blues, and country—and taught himself to play all of them on anything with strings. He was a child prodigy, gigging in country bands around Central Texas before he’d even reached his teens. He was barely eleven when, on December 19, 1952, Hank Williams called him to the stage to play steel with him at the Skyline Club in far North Austin. Two weeks later, when Williams woke up dead in the back of his Cadillac, the Skyline show turned out to have been his final public performance. In Doug lore the night amounted to an anointment.

Through the fifties he recorded country and party rock records with bands like the Mar-Kays and the Pharaohs, but his first real fame came in the sixties as front man and namesake of the Sir Douglas Quintet. That act emphasized the Tex-Mex quotient of his pedigree, most notably in “She’s About a Mover,” an AM radio hit that peaked at thirteen on the pop charts in 1965. The legend behind the record’s creation is almost certainly apocryphal, but also impossible not to repeat: Legendary Houston producer Huey Meaux had grown frustrated with the Beatles taking up all the top spots on the charts, so he’d holed up in a motel room over a weekend with a turntable and their records, intent on cracking the code. He determined that the secret owed in largely to their beat, which he considered a revved-up polka. He relayed this to Doug, and “She’s About a Mover” was the result. But Meaux wasn’t finished. He sent Doug to tour behind the single under the bogus guise of being a British Invasion band—the Sir Douglas Quintet, get it?—complete with Beatle boots, suits and mop-top haircuts. Nevermind that three band members were dark-skinned San Antonio Mexicans, or the little likelihood that anyone confused Doug’s origins the minute he opened his mouth. “She’s About a Mover” was irresistible, a bouncing piece of pop confection that, driven by Augie’s roller-rink organ, became a garage rock anthem on par with “Wooly Bully” and “96 Tears.”

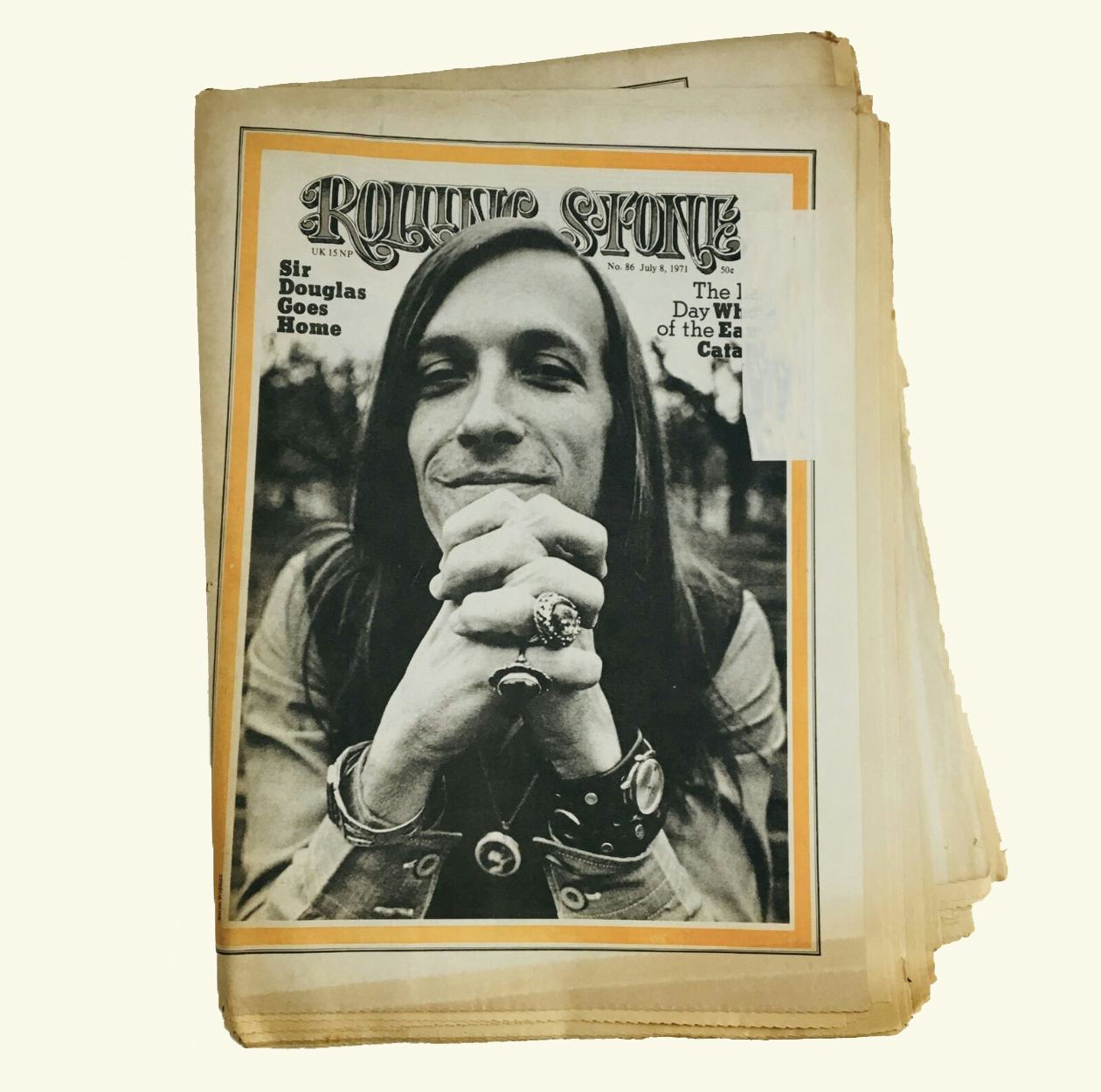

But while riding that high, Doug got busted with a small amount of pot in Corpus Christi. He split Texas and its hardass drug laws to spend six years in self-imposed exile in San Francisco, getting stoned in Golden Gate Park with The Dead by day and adding psychedelic riffs to his guitar repertoire at the Avalon Ballroom at night. He became buddies with Bob Dylan and scored another Top40 hit with “Mendocino,” then wound up on the cover of Rolling Stone. It was a fertile period; he recorded four albums for Mercury records, two of which–Mendocino and Together After Five–were among the finest of his career. But the songs he was writing were mostly about Texas. He missed his old friends and his roots. When his marriage started to falter and hard drugs hit the Haight, the scene got too dark for him. Doug split again.

His return to Texas was news enough for Rolling Stone to put him on the cover again, this time with the coverline “Sir Douglas Goes Home.” The prodigal son was now a bona fi de hippie rock star,his hair grown out and a magnificent pair of bushy, porkchop side-burns hanging from under his cowboy hat like fuzzy dice from a lowrider’s rearview mirror. Visually he was the prototypical cosmic cowboy After a short stay in S.A., where his long hair got his ass kicked by some rednecks outside a taco place, he decided to relocate to Austin.

It wasn’t an obvious choice. Austin hadn’t established itself as a music town yet, but was better known nationally as the place Janis Joplin had left. Since her departure in 1963, most of the city’s younger musicians had followed the national trends, a little folk and a little rock, while the older ones stuck to the traditional Texas strains of country. There was no intermingling; neither camp trusted the other’s sound, look, or lifestyle. But just as Doug hit town a group of kids billing themselves as Freda and the Firedogs got a weekly gig at the Split Rail, a country bar just south of the river on Lamar. They were five adventuresome dope-smokers led by a long-legged piano-player named Marcia Ball, and they weren’t turned off by straight country music. When Doug stumbled upon their Sunday night residency, he found his new home. Freda played the songs he’d grown up on as a kid. He started sitting in with them at the Split Rail and other spots around town, lending guitar solos that, influenced by his Friscoyears, were a little bit longer and a little further out there. Suddenly Austin had its own sound, and its first star.

The most famous music venue in town at the time was the Armadillo World Headquarters. Opened in August, 1970, it had quickly become home for the city’s counterculture freaks. But it was primarily a concert hall for touring acts; the heart and soul of the burgeoning music scene was Soap Creek Saloon, a ramshackle roadhouse hidden in the cedar breaks some fifteen minutes west of town. The surrounding area was officially called Westlake, and soon enough its dense thickets and high valley vistas would become the preferred destination for well-heeled doctors and lawyers making their mass, white-flight exodus from the city. But at that point its residents were cedar choppers and UT professors, open-minded social outliers who didn’t mind the nightly influx of longhairs to the club. Doug felt at ease there too and moved into a two-story stone house on the backside of Soap Creek’s dirt parking lot. His old Frisco friends would crash with him on their way through town, guys like Dylan, the Dead, and Stu and Cosmo from CCR. There were horse stables on one side of the house and raised bait tanks on the other. The landlord, appropriately enough, was a pharmacist.

Soap Creek became the center of the Sahm universe, a summer day-care center for his three young kids, an incubator for new songs he was working up, and a regular stage to play when rent money was due. No fan of telephones, he never installed one at the house, so for quick business like booking local gigs he’d use Soap Creek’s payphone. On at least one occasion, his agent, who was in from L.A., accidently left a brown-paper bag containing a few thousand dollars of Doug’s cash on a picnic table behind the club. A kindly hippie turned it in at the bar.

But Doug was always hustling, always working an angle, and for bigger business deals he’d drive to friends’ houses, from which he’d place surreptitious long-distance calls to his new patrons at Atlantic Records, Jerry Wexler and Ahmet Ertegun. With them he set up the New York sessions that would become 1973’s Doug Sahm and Band, an all-star affair featuring Dylan, Dr. John, and Ray Charles’s old sax player, David “Fathead” Newman, backing him up. Doug had high hopes for the record, which jumped from hardcore country to accordion-driven Tex-Mex to faithful renderings of old T-Bone Walker blues shuffles. Eventually, it would become like a Rosetta Stone for young Texas musicians trying to reconcile the various strains of their musical heritage. But that status was somewhere off in the future. Atlantic released it but had no idea how to classify it, a confusion the label shared with DJs and record buyers. Commercially, it flopped, Undaunted, Doug returned to Austin and settled back in at Soap Creek, cool in his groove and keeping his eye out for a hit.

I learned a lot of that history as an Austin teenager in the early eighties. Even though those were lean years for Doug, for local kids who spent all their time listening to records and talking about music—kids like me and my friends—his name was inescapable. Our fuller introduction came through a band of his disciples, Joe “King” Carrasco and the Crowns, who’d updated Doug’s sound and rebranded it “Nuevo Wavo,” then scored a couple minor video hits in the early days of MTV. On Saturdays we liked to go down to campus and swipe beers from college kids we knew, then run around the Drag pulling Joe “King” flyers off phone poles to put up in our bedrooms. Invariably we’d wind up picking through bins at Inner Sanctum Records & Tapes or Aaron’s Rock & Roll Emporium, and then bug the clerks to play Joe “King” records for us. Every time we asked they’d tell us, “Kid, if you like this music, you really need to get some Sir Doug.” That was our way in.

But my college years at UT were wasted as far as local music went. I spent my weekends crashing frat parties instead of going to shows, knee-deep in a mainstream country western kick that I think of now—with no remorse—as my George Strait Period. Still, I paid Doug the reverence one of the Austin scene’s founding fathers deserved. Occasionally I’d see him in tra c, tooling around town in one of his Cadillacs, and I’d give him a What’s-up? head nod. Or on one of the rare occasions I convinced a date to rack out at my place, I’d take her to breakfast the next morning at The Frisco Shopdiner, where Doug sat at the counter most mornings, pouring over box scores and flirting with the waitresses. “That’s Doug Sahm,” I’d whisper. “He’s a very important man.”

But in the early nineties I started listening to him in present-tense, real time, during his late-career renaissance with the Texas Tornados. They were billed as a Tex-Mex super group featuring better-known names like San Antonio accordionist Flaco Jiménezand South Texas vocalist Freddy Fender, plus Augie and Doug. In Austin, music scene hipsters packed Tornados shows like they’d discovered the hottest new thing, falling for the brown soul vibe and digging on the Tornados’ goofy, Spanglish lyrics: “If you’ve got the dinero/I’ve got the Camaro.” Doug would take the stage like a proper elder statesman, duded up in a brightly colored vest and jacket, with a bolo tie, cowboy hat, dark glasses, and turquoise pinkiering. And he acted like the attention was long overdue. He wasn’t doing anything he hadn’t always done. The wider world had simply returned to its senses.

And as I learned more about the band I realized how central to Texas music Doug was. Flaco was the only accordionist most folks had heard of, having backed up acts as varied as Ry Cooder and Dwight Yoakam. But his fi rst exposure outside the Tejano world had been on Doug Sahm and Bandback in 1973. Freddy had been known as the “Mexican Elvis” when he recorded rock songs in Spanish as a teenager in the fifties. But after serving time for a pot bust in the early sixties, he’d disappeared. In 1974, Doug brought him to play Soap Creek and hooked him up with Huey Meaux, who soon had Freddycut “Before the Next Teardrop Falls.” The song became a million-selling, number one single in 1975.

Tornados had a great run, winning a Grammy for BestMexican-American Performance in 1990, and having a song penned by Doug, “A Little Bit Is Better Than Nada,” play through the opening credits of Kevin Costner’s golf movie,Tin Cup, in 1996. When they started to slow down in 1997, Doug kept going on his own, performing at small clubs around town like Stubb’s inside stage and The Continental Club, and I tried to see him every single time. He’d still keep his band playing long after last call, sometimes going until three in the morning. But his age was starting to show. At a show at the Hole in the Wall in 1999, he introduced a song with a signature bit of name dropping. “This one’s by my old compadre Bob Dylan,” he said, as the band kicked into a slow, bluesy vamp. Knowing he’d never remember the cryptic lyrics on his own, he’d placed a Dylan songbook on a music stand next to the microphone. It was thick as a phone book. And even though Doug had his reading glasses on, he couldn’t find the song. While the band kept playing, he scanned the table of contents, flipped to the index, and then just started turning pages. He searched for a good ten minutes and never did find it. No matter. With the band still going, he stifled a giggle, nailed a couple Freddie King licks to segue into another number, and stepped back to the mic. “Here’s a hit by my old friend, Roky Erickson,” he said. “Roky, this one’s for you, brother. It’s called ‘You’re Gonna Miss Me.’” The crowd erupted like Roky had just entered the club with Dylan on his shoulders. That ended up being the last Doug show I ever saw. A few months later, in November, Doug bolted on one of his frequent, spur-of-the-moment trips, this one to New Mexico. The newspaper would later report that he’d called his son on his way out of town to let him know he was leaving and casually mentioned he was suffering a little indigestion. But later that night, at a Taos motel called the Thunderbird, he had a heart attack and died. He was just fifty-eight.

Word spread through Austin the next afternoon, and that night we three buddies of the West Texas road trip assembled to pay our respects. We made stops by Antone’s and The Continental, the two clubs where we’d seen Doug play the most often. But their scenes were too somber, and we knew that a random, previously-booked band doing a couple Doug covers wasn’t going to take us where we needed to go. We hopped into that same old Land Cruiser and started to drive. We played some Tornados, then ventured back in time to “Mendocino” and “Nuevo Laredo” and “She’s About a Mover.” Finally we landed on “At the Crossroads,” one of the songs Doug had written while he was out in California and pining for Texas. “You can teach me lots of lesson, you can bring me lots of gold,” he sang. “But you just can’t live in Texas if you don’t have a lot of soul.”