A BASTION OF SOME OF THE COUNTRY'S LAST TRULY DARK SKIES, TEXAS IS THE PLACE TO LOOK UP AND SEE WHAT THE UNIVERSE HOLDS.

Many years ago, when I still held my old religion with a pinky tip, I joined a sister-friend for Watch Night service, in Harlem. That night, her pastor, Pastor Mike, revealed his theme for the coming year: “I Am the Dawn and the Dark,” inspired by the creation story, found in those first few lines of Genesis:

"In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. Now the earth was formless and empty, darkness was over the surface of the deep, and the Spirit of God was hovering over the waters. And God said, “Let there be light,” and there was light."

At First Corinthians, Pastor Mike’s church, you’ve gotta stand for the reading of the Word, and so we stood and they read and I considered my long train ride back to Brooklyn until, eventually, Pastor Mike commanded: “Now read that again.” I joined this time. Pastor Mike then read again, alone: “And the spirit of God was hovering over the waters. And God said, ‘Let there be light,’ and there was light. There was a long, tense silence in the sanctuary. “Now where does it say God made the darkness and called it bad?” he asked. Nobody answered. “Don’t you see?” he cried. “God was in the darkness.”

Pastor Mike looped in my mind recently as I leaned against my car on the side of a two-lane rural road, next to the locked gate of a state park called Enchanted Rock. I had chased the stars out there, to the Texas Hill Country, to this rock that folks have visited for more than 10,000 years: long before Texas, long before Genesis. Nearly every people has its Genesis, some way to make sense, or at least a compelling myth, out of The Great Whodunnit. Who might be Olodumare (Yoruba) or Sky Woman (Iroquois) or Mireuk (Korea) or Tiamat (Mesopotamia). Who might be Twins or a Raven or a Random Bang. But It always includes creating stars.

I chased the stars out to Enchanted Rock, and around 9:30, I cut my engine. I could see no light except the dim orange traffic sign warning away park visitors without reservations. I could hear no sound except the crickets taunting me through some nearby forest megaphone.

You’re finna die, the crickets chirped.

It had been three years since I first felt this darkness panic, in Terlingua, roughly 15 minutes from the Rio Grande, 10 or so from Big Bend National Park. I’d driven the lonesome highways from Brooklyn to Nashville, Nashville to Dallas, Dallas to Far West Texas. By the time I dipped off I-10, just past Fort Stockton, darkness was rising from the east, though there was light enough to see my first roadrunner and the Chisos Mountains across the desert plain. The two-lane strip of road ran straight enough to close my eyes and pray.

My family’s been in Texas since before the Civil War, but I had never traveled so far west and south inside my state, and no one had prepared me for the darkness in the desert, for the sense of terror that darkness struck in me. Out there you can’t fathom who or what is watching you from where. Add to the dark a quiet so complete, so disorienting that even familiar sounds take on a sinister enormity. Each rustling leaf a mountain lion. A lurking wildman. This is the terror of the strange and silent darkness—at first.

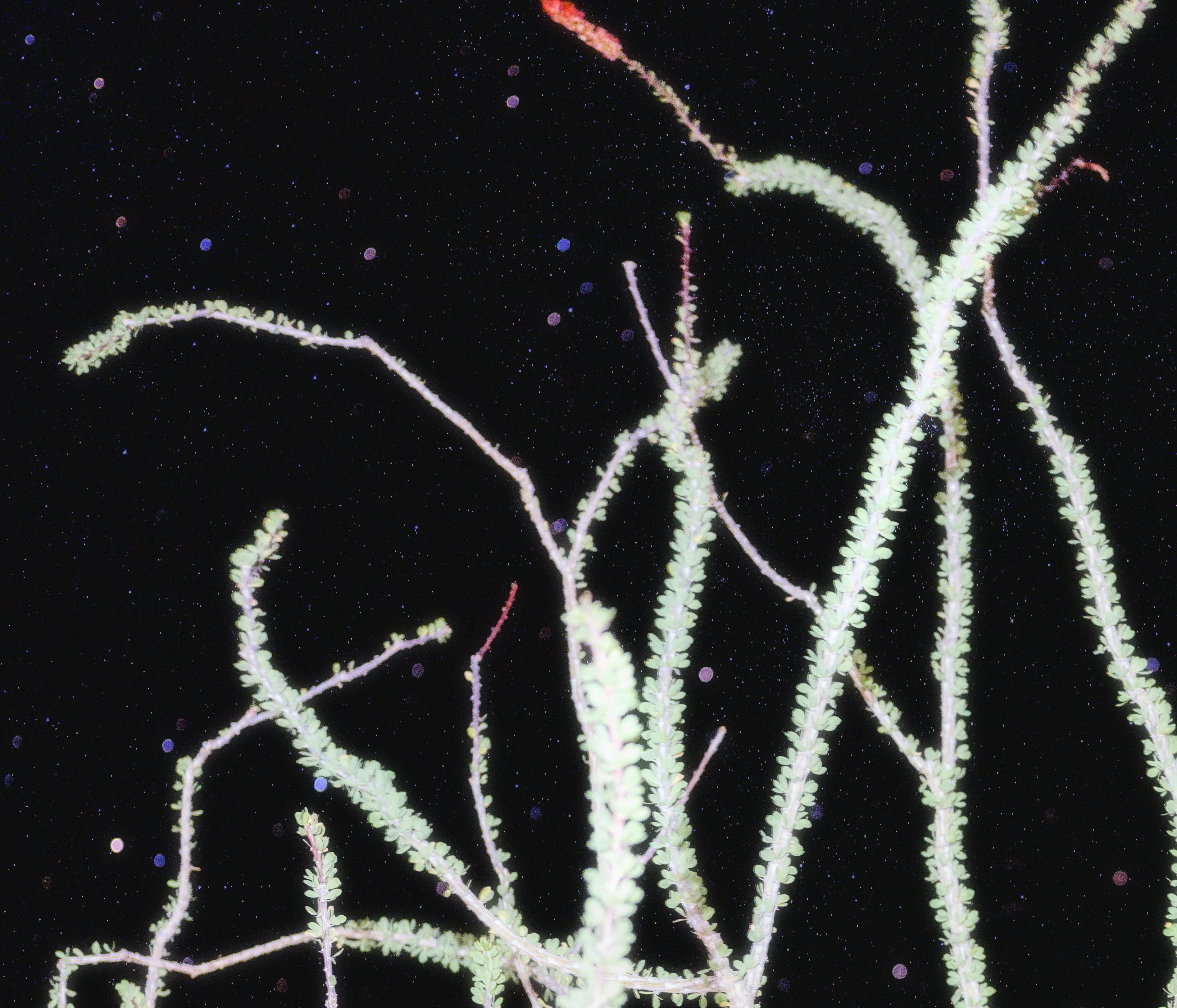

When I finally looked, that first night in the desert, I almost gasped: I was standing face-to-stardust with the Milky Way. What manner of milk is this? I wondered. If you’ve never seen the Milky Way, I’d say: Imagine not milk but an unhinged electric rainbow, liberated from its cosmic corset, bending its wide translucent back across the night sky, horizon to horizon. Even in the Hill Country—less remote, a less-dark darkness—the night sky soon reveals faint traces of our galaxy. It strikes me that the Milky Way is not something out there but something we are in, the speckled multicolored iris of a giant eye, staring out into the universe as I stare out of It, the eyeball of the world.

After going back to Far West Texas for three years, I can now remind myself: Our eyes are built for darkness too. If we simply give our pupils a chance to open wider, let our retinas’ sensors switch to low-light mode, we will see. We will know. Not everything, but more than we expected.

Outside Enchanted Rock, I again followed that Great Way of Milk toward the moon. Halfway between eclipses, halfway between new and full—though to itself the moon is always full. We’ve always seen the heavens on our terms. And for the past few years, I have sought and found a buddy in Jupiter, one of the brightest objects in the night sky.

Sao, my astrologer, once told me, “Jupiter is the most fortunate planet in our solar system.” At the time, I was preparing for my Jupiter Return, a 12-year cycle that begins when Jupiter shines again from where it shone during your birth. “You’ll encounter opportunities, plural,” Sao told me, “to expand your wisdom and your clarity and understanding of what your personal truth is, how to live.” He advised me to build my psychic muscles every day. A meditation class. Prayer. “You’ll find something,” Sao reassured me. “Just ask Jupiter.”

Jupiter led me to Enchanted Rock, against my doubts. All day and night, under cloudy skies, every stargaze forecast read poor. On the way, all I saw through my windshield were glimpses of the smothered half-moon. Stop wasting gas, part of Me told myself. After all, I’d already done enough “research.” Two nights before, I’d climbed onto a roof at the University of Texas and looked at Saturn through a 16-inch reflector telescope, aided by a verified star guide. The following afternoon, I’d returned to campus for a panel on cosmology and free speech. I learned about dark energy, about how we have no clue what this universal darkness truly is. “We call our ignorance ‘dark energy,’” one of the experts said.

I eased off onto the dusty shoulder of Highway 290, just shy of Johnson City. Wanted to inspect the sorry sky one last time. I checked for zooming headlights. Hopped out and scanned the dust for snakes. Stood kinda still, lazily looked up toward the wide Hill Country sky.

Oh.

There was Jupiter, my bright and evening buddy, blasting down on me through all the haze and darkness. I assumed by this He meant: Keep going.

Alone outside Enchanted Rock’s locked gate, deep in the 10 o’clock hour, I watched clouds cling to the night sky like mounds of bubbles in a dirty bath. I searched their thicket for more cosmic vittles. I waited. I breathed.

Moon. Milky Way. Buddy. Between the moon and Jupiter I saw a slightly tinted starlike thing. I hurried to the Night Sky app, a sort of live-action Wikipedia for stargazing, then held my phone up to the sky until I got confirmation. Okay, Saturn! Oddly, Saturn looked much better at a distance, as a bright, vague dot. I’d asked the UT star guide what people say when they first glimpse Saturn through the telescope. “It looks fake,” she’d answered. “It looks like a hologram. Emoji.” The great machine even obscured Jupiter’s glamor. The Greek word telescopos evidently means “far looker.” Far looking, by another name, is prophecy. And have not all the prophets preached that sight and vision are not synonyms?

“How do you find a galaxy?” I had asked another star guide on the roof. The star guide hustled over, pushed his finger into the sky, toward something called the Great Square of Pegasus. “Off the end, there’s an arc,” he said, trying to show me. “There’s a dim star right there. It’s hard to see. There’s another, dimmer star, which you can’t see, and then there’s the Andromeda galaxy.” I didn’t see a thing. Andromeda is our nearest galaxy, two million light years away in normal traffic. A light year is six trillion miles. “If you were in dark skies,” the star guide explained, “you’d see star, dim star, and really dim star, plus the galaxy all together. They’d all be naked-eye visible.”

In his book The End of Night, Paul Bogard warns that 80 percent of kids born in America today “will never know a night dark enough that they can see the Milky Way.” Blame our obsession with electric lights, half of which shine down on parking lots. What havoc have we wreaked with our modernity? We’ve jammed illumination into damn near every dark place we can find. Hung cameras and created apps to warn us of monsters. Alerts straight to our phones, 24/7. All alerts the same great cry: Help! The same great question: Is anybody out there? Well, in the Milky Way are 100 billion stars. Among these stars there are at least 100 billion planets. Beyond our galaxy, perhaps 200 billion other galaxies, and that’s just counting the observable universe.

“It hurts,” lamented a friend when I passed these facts to him. “The scale of the universe … our brains … my brain … I can’t contain it.” It probably hurts because we’re not meant to contain it, to fully comprehend our universe. Some things are best loved as a mystery, not a puzzle. And yet, I have learned, we do contain it. The calcium in our bones. The iron in our blood. All formed from stardust, literally. What else is there to say but wow?

"WHEN I FINALLY LOOKED, THAT FIRST NIGHT IN THE DESERT, I ALMOST GASPED: I WAS STANDING FACE-TO-STARDUST WITH THE MILKY WAY."

As night spun toward morning, I glimpsed, past Jupiter, a cluster of deep-blue glowing orbs. I mean like perfect Yves Klein blue. Not even in Terlingua had I witnessed such a thing.

I fumbled for my phone, raised the Night Sky app desperately toward the orbs. My camera picked up every undesired cosmic speck until, 119 seconds later, a small icon popped onto the screen.

“The Pleiades!” I hollered, my startled joy so deep, so liquid, it filled all the spaces normally reserved for self-consciousness. I speed-scrolled over Night Sky’s words: “The Pleiades, or Seven Sisters, is among the nearest star clusters to Earth … dominated by hot blue and extremely luminous stars that have formed within the last 100 million years.”

“The freakin’ Pleiades,” I whispered, in a giddy gahlee voice.

There are thousands of years of stories told about these blue stars. They were known and named by the Greeks, by Aztecs and Cherokees, by Persians, Celts, Egyptians. Aboriginal Australians placed the Seven Sisters in the Dreaming, their multifaceted cosmology. Hindus called the stars Krittika and linked them with the Hindu war god. The Babylonians called them “star of stars.” In Japan the stars are Subaru. The Universe has no need for brand consistency. It welcomes any story of Itself, the best of us and the worst. Perhaps because It knows a startling truth: When we look up at the night sky, we are seeing how things used to be, gazing into the past. Andromeda, to your naked eye, tonight, is actually light Andromeda threw off two million years ago, finally reaching us on Earth. Our great-grandchildren’s great-grandchildren might see tonight’s Pleiadian light. “Call me anything you want,” says the Universe, “I’m already something else.”

It hurts, I thought, as I took in this fact. I read Night Sky again: “The Pleiades will not stay gravitationally bound forever. Some component stars will be ejected. … Others will be stripped by tidal gravitational fields.” I closed the app and dropped the phone in my back pocket. Clouds began to smother more of the stars, like a great plague fog over a celestial city. The moon drowned in its dirty bathtub. I kept my gobsmacked eyes on those hot-blue orbs.

I wondered how sad Einstein felt when proof arrived that the universe was expanding. Expanding faster as it expands, in fact. Initially, Einstein had believed the universe was static— so fervently that he added a mysterious factor to his theory of general relativity, just to make the math check out. He called this factor the “cosmological constant,” right up until 1929, when he reassessed, calling the cosmological constant his “greatest blunder.” But nearly a century later, scientists essentially explain why the universe is expanding by adding a cosmological constant right back in. Einstein’s successors call the mystery factor “dark energy.” Pastor Mike’s colleagues might call it “God.” My bet is that they all just want to know: How does It end?

“Now what ex-act-ly are you gone be doing in the desert?” my grandmother Dorothy asks each time I head out to Terlingua. I’ve never lied, but for some reason she never seems convinced by “artist residency” or “working on a project.”

The last time Granny asked, we were alone in my car. I’d been thinking of the things I’ve written here, and so I told her: “I just go to see the stars sometimes.”

I told her that I’d seen the Milky Way up close—even saw, on that first trip, a storm of shooting stars. We’d built a fire in the yard of Willow House, my friend Lauren’s casita retreat, to sit outside and watch the Perseid meteor shower. The shooters looked like zooming lightning bugs or cue balls whacked supersonically across an eternal pool table. And the later it got, the more there were.

“It was crazy,” I told Granny.

“The stars,” she sighed, as if she’d glimpsed them from the passenger’s seat. I asked whether she’d ever been to any desert. “I never even been to Houston,” she joked. “I been in Dallas, Texas,” where she lives, “and Massey Lake, Texas,” where she was born in 1936 and lived as a little girl. “But down home we had that big ol’ porch, over at Uncle Jamie’s,” she remembered, gripping her seatbelt with both hands. “You know Uncle Jamie.” I did. “And when I tell you we would just sit out on that porch, every night we could, and just look at all them stars. There was stars and stars and stars.”

She’d never told me this, and honestly it never crossed my mind that she’d experienced such a thing. In Massey Lake, my grandmother and her kin rode wagons, when they didn’t walk. Used an outhouse. Picked cotton and their own fruit. Used kerosene lamps and candles. And yet, in her brief country childhood, with so few modern luxuries, she’d seen more stars than I may ever see. She helped me grasp another reason I return so often to the desert: to remember that a shooting star is no rare thing. There is enough, the night sky tells us, and more to come.

From one angle, the cosmos seems to be growing apart. Even the moon is slowly floating away from Earth. But then there is Andromeda, which we expect to crash into the Milky Way within three billion years. Both will be destroyed, or reborn as a New Thing, depending on who tells the story. The stars remind us not to waste our lives with worry. It all ends the same way, every time: dust and gas and darkness and, maybe, light again.