I WAS IN the eighth grade when I moved to Albany, Georgia, from Fort Belvoir, Virginia. It was the end of February 1998, and when the plane landed in Atlanta, I stumbled off in a gray Chaps shirt and worn black-and-white Reeboks. Dazed, I tugged at my wrinkled shirt. “Coulda had a Polo,” a classmate snickered two days earlier as I’d walked through the halls of my middle school one last time before moving to the Deep South. I’d chuckled nervously as she sashayed off with a boy I used to like. Bitch.

I was moving to Albany to live with my grandparents with the hope that I could start over and recover from my mom and stepdad’s divorce. I grappled with the anxiety that their breakup was somehow my fault. Guilt about moving to Georgia and leaving my brother and sister behind ate away at my spirit. I fumbled for a greeting the same way I had fumbled with that childproof orange bottle cap a year before, desperate for relief from daily school bullying.

“Hi, Nana. Paw Paw.” Even though my words were flat, the slight crack in my voice revealed the anxiety simmering underneath. My grandmother embraced me, and I slumped over her shoulder like an oversized baby, collapsing. There were few words between us.

“Hey dea, Lou! Let’s get your stuff and go home.”

Paw Paw squeezed my shoulders and gently pushed me in the direction of the train that led to baggage claim. The computerized voice on the “plane train” was dry but not as robotic as I remembered. Nana looked at me intently, smiling every time I met her eyes. Paw Paw stood right next to me, as if protecting me from the world. My chest heaved as I inhaled. I shuffled my big feet out of the way of other passengers, certain that every glance or whisper was about me. I was a tall, lanky and awkward 14-year-old Black girl.

The Atlanta sun was extra bright outside the airport, promising something new. Years later, I realized why the sun shone so brightly for met hat day. Atlanta was the beginning of a promise: It was my opportunity to get it right. Georgia’s pace would force me to slow down and pay attention to myself and how I moved in the world around me.

FIELD GUIDE

Atlanta

Civil rights history and city parks, barbecue and cocktail bars, hip-hop heritage and architectural lore.

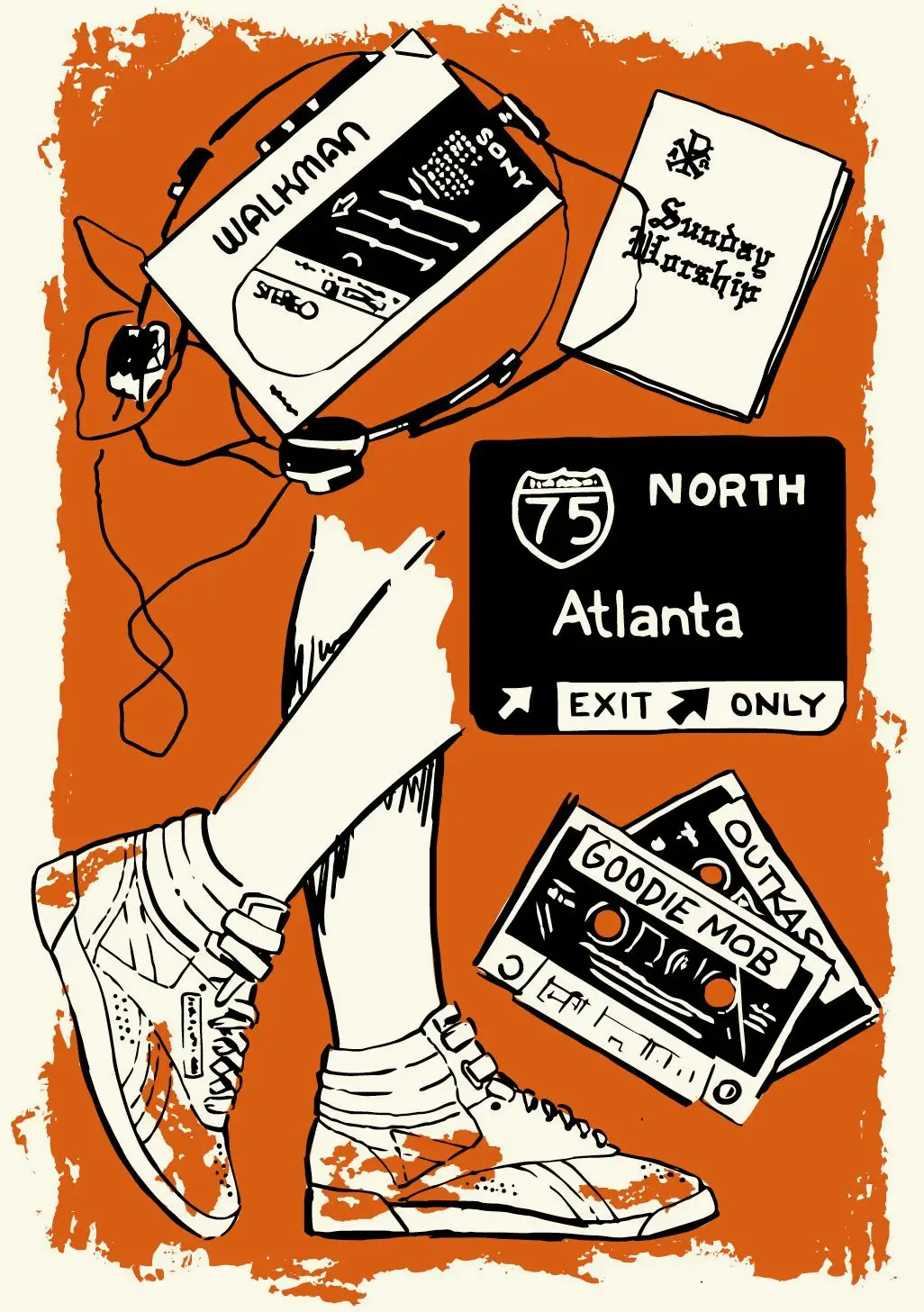

I squinted and unsteadily bumped against Nana on the ride to my newhome. The drone of airplanes overhead did nothing to quiet my thoughts. In my grandparents’ shiny black Lincoln the comforting scents of BlackIce car freshener, soap and Poême perfume mixed. Cracked-leather seats succumbed to my weight with a light burst of air. My grandfather put on a gospel tape as we turned out of the airport parking lot. The Canton Spirituals. “I’m Coming Lord.” “Fix It Jesus."

I’m Southern now.

Albany is about 50 miles off Interstate 75. Unlike the busyness of Atlanta, with its tall buildings and concrete mazes of highways, the way to Albany was flat, quiet and increasingly empty, subbing trees and crops for buildings the farther south we traveled. The drive was full of unincorporated towns and what could pass as haunted houses and cemeteries. There were ghosts on that road that would never get to tell their stories. I often wonder how many of those ghosts were Black. It’s easy to disappear in southwest Georgia. On the day of my arrival, we were welcomed to town by a slightly bent Dougherty County sign, a bullet hole through its center. The Black music stations started to come in more clearly through the radio.

It is not pronounced “All-bunny” like its New York State sister city. The drawl is hard. It is demanding and present: “Awl-benny.” The Flint River slices the city in half. “The Eastside is the nigga side,” Paw Paw would often fuss. “Don’t go over there.” A rickety train bridge glides over the rocky part of the river. The river stinks. No one can pinpoint what kind of stank is in the Flint. But it is an old, historical stank that renews itself with each rush of water over the rocky riverbed. The Flint is the same river that God tried to wash us out with, not once but twice. We stayed put like red clay on fresh white Reeboks.

My new home was out past the city limits, almost to the line where Dougherty County became Mitchell. Men got dragged to their death in Mitchell. Up the road there were two working plantations.

I would fill that summer before high school with homemade mixtapes and by walking the roads by my house. Mixtapes full of OutKast, Three 6 Mafia, Goodie Mob, Lil Will and Lil Jon and the East SideBoyz blasting from my Walkman. Those tapes would die cruel deaths, the thin strips snapping after repeated rewinding so I could stop to learn a line or where to emphasize a curse word. I’d jig awkwardly past the trees and sing the lyrics to cicadas, who’d sing back unamused. Goodie Mob’s “Black Ice” and “booty shake” music made every single one. While it wasn’t perfect, Atlanta was the “big city,” full of dope Black people doing dope shit on their own terms. When people wanted to escape the country of Albany’s landscape, they ran up 75 to Atlanta. Listening to that hip-hop made me realize how big the city really was, peppered with different neighborhoods, zones and folks. It was easy to get lost in their stories–getting lost in Albany was more difficult. Everybody knew PawPaw and Nana. With the exception of family, nobody knew the Barnetts in Atlanta. Although I couldn’t physically get there, listening to Atlanta rap was the anonymity and escape I felt I desperately needed.

“'The South got something to say' suggested that the paranoia of the past, which kept Black people alive, should not drown out the concerns of the present. There is still unfinished business that needs to be aired out and addressed. The younger South got something to say, myself included.”

My mixtapes were distinctly Southern and conjured new ideas of happiness in my heart and spirit. I couldn’t articulate it then, but I was using them to heal myself and ease my anxiety. To riff on Toni Cade Bambara and the theme of healing in her novel The Salt Eaters, I frequently questioned whether or not I was ready to take on the burden of being well. The pain of healing meant confronting what felt like eating salt with cracked teeth: the sting of my folks’ divorce, the uncertainty of being a Black teenage girl about to start high school and realizing that my plans for my own being were trying to blossom in the long shadow of my grandparents’ loving and high expectations. Southern hip-hop was a different type of salt-eating. As a rural Black Southerner, we were communal, jointly struggling to find our own unique identity and discourse. Being well for my grandparents was a silent struggle–just stand and God will fix it. But this hip-hop suggested that wellness was messy, janky and an ongoing process. I was experiencing the rural annals of what Atlanta rapper and East Point native Cool Breeze coined “the dirty South.” Like me, my people’s legacies reached deep into the dirt. I came from dirt folk who worked the lands in hopes of cobbling together a comfortable and successful life. I lived in the interstices of a post-civil rights landscape and the freedom dreams that older generations–absent the tangible Jim Crow biases–expected my generation to achieve. Atlanta hip-hop duo OutKast opened the door for a nation to see that the South does, and did, go on after the civil rights movement. They introduced the concept of OutKastedness as not only a creative meme but an act of self-care. Their creating of work outside the fringes was a conscious effort to place their agency and desires first. Southern rappers, especially OutKast, created a blueprint for not only functioning and existing in the region, but living as a collective in an often self-traumatizing space.

At the 1995 Source Awards, after winning Best New Rap Group, André 3000 (André Lauren Benjamin) responded to a booing, predominantly East Coast crowd with, “the South got something to say.” Benjamin’s emphatic statement declared his worth and validated his roots as a renewable source of inspiration. However, Benjamin’s statement can also be read as a mantra for wellness, an acknowledgment that the pain and experience of the past do not trump the pain and optimism of the present. They often overlap and inform each other. “The South got something to say” suggested that the paranoia of the past, which kept Black people alive, should not drown out the concerns of the present. There is still unfinished business that needs to be aired out and addressed. The younger South got something to say, myself included.

Hip-hop helped me carve out a space to let my wounds breathe and scab over. Yes, I still catered to my grandparents’ expectations of salt-eating–church every Sunday and family prayer sessions–but hip-hop saved my Southern Black girl self. Indeed, when André 3000 interrogates his schoolgirl crush Sasha Thumper on “Da Art of Storytellin’ Part 1” and she responds, “Alive,” tears welled in my eyes because for a long time I felt like Sasha (and knew a few Suzy Screws, too). Would I live to tell my own tale? I wasn’t unfamiliar with suicidal ideation. Like Sasha Thumper, I thought for a long time that daring to dream and speak myself into the future was a privilege too heavy for my jaws.

And, like OutKast, I found the courage to will myself into existence. The awkward 14-year-old girl grew into a proud Southern Black woman who ran back toward Atlanta to work, live and teach. The late 1990s Atlanta that comforted me and filled my imagination was gone. Atlanta was no longer just the big city for rural folks like me but everybody else. Paw Paw passed in 2009 while I was working on my doctorate, 11 years after that trip home from the airport. Nana Boo and my auntie Dee still live in Albany. When I drive home for a visit, I’m surrounded by those same unincorporated towns and cemeteries that caught my attention on that first drive as a newly initiated Down South Georgia Girl. I think about the girl who walked the dusty-red country roads by her grandparents’ house listening to Southern rap. I want her to know that her adult self still listens to be well.

About the author

DR. REGINA N. BRADLEY is an assistant professor of English and African diaspora studies at Kennesaw State University, the co-host of the podcast Bottom of the Map and the author of Chronicling Stankonia: the Rise of the Hip-Hop South.

DR. REGINA N. BRADLEY is an assistant professor of English and African diaspora studies at Kennesaw State University, the co-host of the podcast Bottom of the Map and the author of Chronicling Stankonia: the Rise of the Hip-Hop South.